Study visit to the Netherlands and Belgium 22–25 April 2025

Knarrenhof Ridderkerk in Rotterdam

The block with 21 owner-occupied homes, six social housing rentals and a community house surrounding a common yard was completed in 2024. Knarrenhof is a national foundation which has realized 17 housing communities since 2010 in cooperation with older people who want to keep track of each other. Members are offered housing accordingly, in Ridderkerk there were 560 people on the list. The housing has two floors with internal stairs, but you can live only on the ground floor if necessary. Ridderkerk is 45 minutes by public transport from Rotterdam city center in an area with lower land prices, but still just 15 minutes walk to the center of Ridderkerk. Knarrenhof bought the land from the municipality at half the market value, taking into account that Ridderkerk creates social benefit by realizing housing for the elderly and for low-income earners. The social benefit consists of integrating social housing, managed by Wooncompas housing association, but Knarrenhof also applies a price cap on the owner-occupied apartments, which are 20% cheaper than the market. When people are selling, Knarrenhof sets the price and the next person in line is offered to buy. The fact that municipalities sell land at a low price is questioned by private entrepreneurs but as this is permitted in social housing projects, legal trials have not led to any projects being stopped. Knarrenhof’s concept is popular, nationally there is a queue of 55,000 members. Municipalities are also positive as the need for home care is decreasing in areas where Knarrenhof is located and as social housing is being integrated. Links: ↗ ↗

Markthal in Rotterdam

This spectacular market hall is located in the center of the city and was built in 2014 as part of the city’s effort to build iconic buildings to attract both the middle class and tourists to the working-class port city of Rotterdam. The market hall was packed with people and houses a wide selection of shops and restaurants, but apartments have also been built around the entire hall. In the basement there is a large grocery store and parking, as well as a floor for culture where historical remains have been excavated and can be viewed. We mainly visited the Markthal to have lunch – the housing here is not an example of a co-building project and is not affordable, although rental apartments are directed at the middle-income segment. Still, it is fascinating to see what free thinking about housing design can mean. Investing in iconic buildings seems to have had a major positive effect on the city’s economy. However, one should be aware that it is a conscious strategy on the part of the city to gentrify the center. In one of our previous research, interviews ten years ago showed that the municipality was striving to reduce the proportion of social housing in Rotterdam from 80% to 60%. Increased tourism was part of this, but also major investments in building apartments in high-rise buildings in the city center and on the piers in the harbor, for the middle and upper middle class. Their hope was that the proportion of the working class and social housing instead would increase in the municipalities around Rotterdam. Links: ↗ ↗

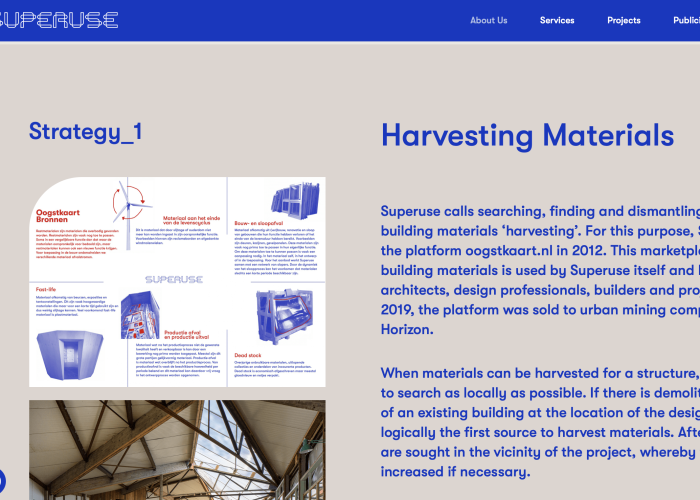

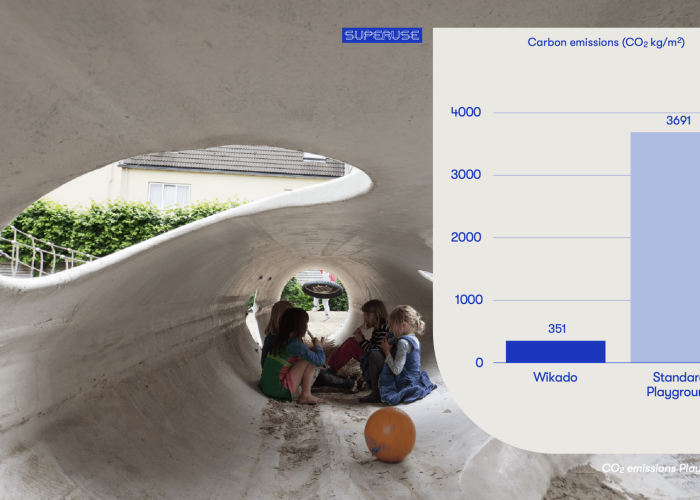

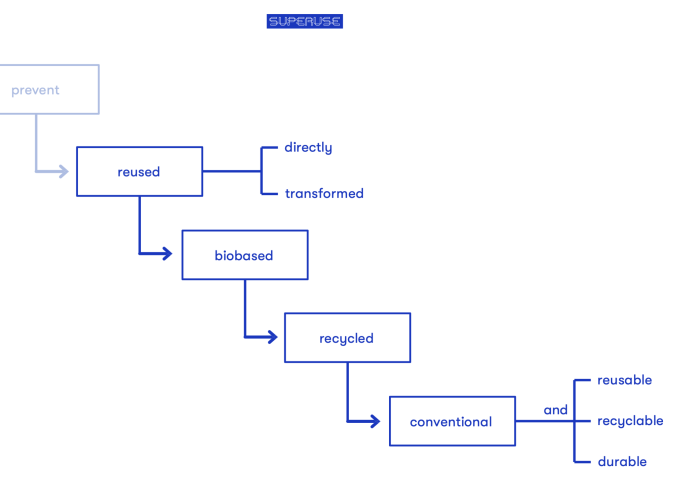

Superuse Studios in Rotterdam

This architectural office has a far-reaching strategy for reuse, circularity and minimal climate footprints. It involves, in order of priority: reuse of entire buildings; harvesting of building materials; design based on such harvesting; dismountable materials; circularity of materials and circular building process. Engineers ensure that constructions using recycled materials are approved. The sustainability goal includes affordability and used materials are often much cheaper than new. We got a presentation about Housing Cooperative Boschgaard – a transformation of a former community center into 19 resident units completed in 2024. The community center was occupied by inhabitants and Superuse collaborated with them, commissioned by a housing coorperation. The process took seven years and not all inhabitants stayed on. They were 10-15 persons at the beginning, only 4 in the middle of the process and then grew to 39 in the end. The housing became affordable, all apartments are social housing with permanent contracts and rents within that framework. The CO2 savings were 70% compared to the current building standard and 84% of all materials were reused while the national average does not exceed 8%. The cooperative is very popular among municipalities but has not yet had a successor. It is easy to do, says Superuse, but there is a radical stamp that scares a little. Links: ↗ ↗

Wallisblock in Rotterdam

This residential block is located in Spangen, a stigmatized area with a high crime rate. In 2003, the municipality implemented the idea of donating an extremely neglected housing block to a group of inhabitants in exchange for them investing €1,000 per square meter in renovation; managing the process together; starting within a year; and settling in for at least two years. Before the purchase, the municipality invested €5 million in foundation reinforcements and the group received support from an architect. This was the first collective housing project in the Netherlands where no developer was involved. Through dialogue, the architect managed to shape the area so that all 40 households were satisfied. Patios are open onto the large common courtyard and there is a smooth transition between the private and the common area in the middle. The renovation cost was €70,000 for a smaller apartment and €200,000 for a four-story apartment, the residents believe it is affordable but you needed to have the ability to get a loan or owning a home to sell, there is no social housing in the block. The municipality was satisfied with the process in Wallisblock and continued to offer housing groups to take over buildings – in 2008 they had completed 169 projects. On the other hand, none of them are like Wallisblock, says our host, she does not know of any project that has been implemented in such a heavily stigmatized area and changed its reputation. Links: ↗ ↗ ↗ ↗ ↗ ↗

Centraal Wonen in Delft

Central Wohnen, a movement to promote collective housing, was started by a woman who saw collective housing as a way to promote women’s emancipation. Centraal Wonen in Delft was realised in 1981, built and owned by a student foundation. The 100 residents are covered by social housing regulations. Tenants were involved in shaping the project in design workshops. Everybody has access to a large community room with kitchen, which is also rented out and a common garden is maintained through their association. The collective has no ordinay flats, residents can rent 1-3 private rooms in 13 residential groups, all with a shared kitchen and living room. Toilet and showers are shared and there are also small kitchenettes on each floor. The groups form four clusters, each with a small garden, bike sheds, work shop and laundry. The average residence time is seven years. The cheap rent is a strong driving force for moving in and many students come, there is a great diversity. The houses are old and quite worn down with a simple standard of living. It will shortly undergo facade renovation which will increase the five centimeter insulation in the walls. Sharing kitchen and bathroom may be strange to some nowadays but can be seen as a modern answer to the climate crises, resource shortages and increasing feelings of loneliness and mental illness. Residents of all ages enjoy themselves very much here, according to the architect we met, who himself was part of realizing this collective housing. Links: ↗↗↗↗

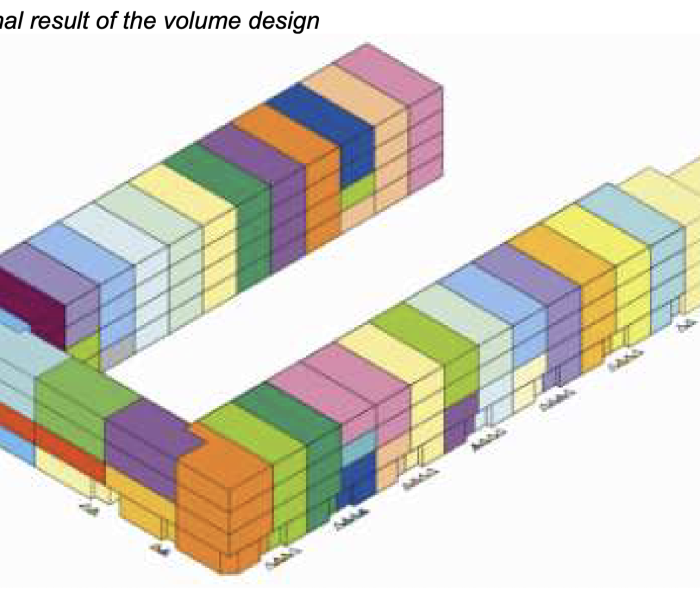

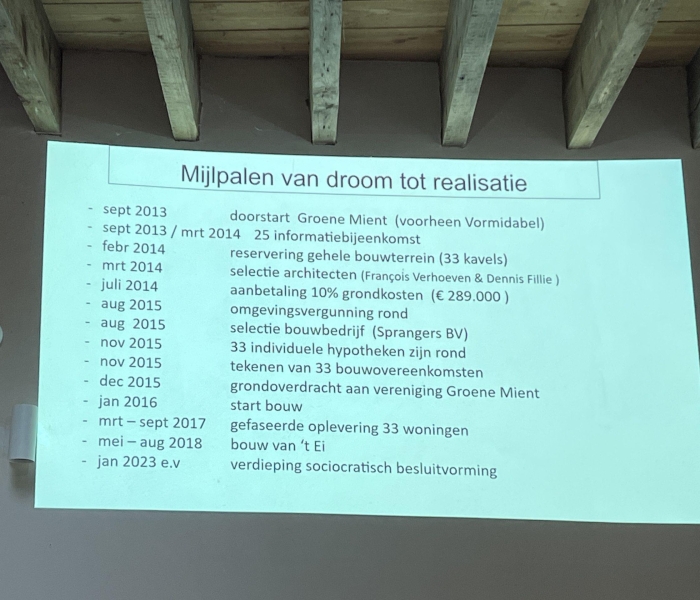

Groene Mient in Hague

This inhabitant-driven project started in 2007, by a group striving to live together in solidarity in ecological, affordable, accessible and flexible housing. The municipality wanted to sell a former school site subdivided into traditional plots but found more security in working with a group organized as a CPO-initiative (Collectief Particulier Opdrachtgever meaning collective private commissioning). The municipality therefore supported the CPO with €20,000. The result after 10 years is 33 owner-occupied homes in climate-neutral buildings and a community garden managed through permaculture principles. The houses are well insulated and some have geothermal heat pumps. They each paid an initial cost of €20,000 to cover project costs, piloted by an organization called Building Community. A German bank provided individual loans covering 90% of the building costs. A community house was built by the residents, owned in a joint property association like the garden and the solar panels. When people move, they can choose buyer and price but the new owner is obliged to accept the community rules. Groene Mient is an interesting combination of private and common ownership. The organization is reminiscent of a condominium association but with high ecological and social ambitions. The municipality’s support with funding and land assignment to a group is interesting, however, we do not believe that the housing has become particularly affordable, as the residents had to bear the main burden of the economy and there is no social housing in the block. Links: ↗ ↗ ↗ ↗ ↗

The New Farm in Hague

This is a former industrial complex with 9,000 square meters that has become a center for sustainability, circular economy and social entrepreneurship. The building was raised in 1958 as a Philips factory and was empty for a long time before new businesses moved in. A rooftop farming project in 2016 did function well for a while but was closed down due to high costs. Since 2019, architect Corine Keus has led a transformation of the building into an active innovative space. The municipality owns the building and is financing the transformation, partly supported by EU funds. Today, the building houses over 50 companies with an environmental and social focus, such as food production in the form of a bakery and a brewery, as well as recycling companies and circular startups. One manufactures new products from old work clothes and also offers jobs to people far from the labour market. The building also houses community spaces, offices and a restaurant. There are solar cells on the facade, flexible spaces and the winter garden on top of the building has great potential. It is interesting that an original factory can house many different functions and unusual that the municipality has been such an engaged part in finding new ideas and uses. As you can read under the heading Superuse, reusing existing buildings should be a priority when it comes to reducing our climate footprint. Links: ↗ ↗ ↗ ↗ ↗ ↗ ↗

Cooplink

Cooplink is a knowledge network for housing cooperatives in the Netherlands, supported by the ministry for internal affairs. Our presenter is part of the board, working as a volunteer for the network. The housing cooperative movement is growing quite quickly in Europe. In the Netherlands they have VrijCoop who, like Mietshäusersyndikat in Germany, finances housing cooperatives and also protect buildings from being sold on the market. Housing cooperatives are not necessarily cheap to live in to start with, but once they have payed off their loans after 30 years, it can become really cheap. If it is to be affordable for residents from the start, municipal support is needed in the form of allocation of land to cooperatives at discounted prices. Amsterdam is now at the forefront of such a development but several other cities are also active. There are also housing cooperatives initiated by low-income residents but managed by entrepreneurs that gettin financial support from the governmental social housing system. Cooplink focuses on the third sector, as housing cooperatives are part of civil society, and develops and exchanges knowledge with them about existing barriers for scaling up and what changes are needed for success. This knowledge is shared with the government, municipalities and financiers and is expected to change their view of the role of the third sector in housing provision. Links: ↗ ↗ ↗

Grote pyr in Hague

This former school building from 1907 has been transformed into a residential building and work place. The background was that the municipality had occupants in another building that they wanted to access, and these people were therefore in 2003 offered to live here instead. In collaboration with the municipality, the collective formed a foundation – the Wonen Werken Waldeck Pyrmontkade – and began converting the building. Today, it accommodates around 50 persons in 25 rooms and 20 companies. The tenants rent their rooms within the framework of social housing which implies afforable living costs; our host pays 190€ for her room. They share kitchen, toilet and shower and the standard is low. Self-management is central – the tenants are members of the Grote Pyr association (which also governs the foundation), participate in meetings and carry out practical work taking care of the building. They have developed the building a lot and made it nice and well-organized. Now they are faced with a need for additional insulation of the single-glazed windows. They are heating the building with wood stoves and this is time consuming. Municipal and state funds have been combined with the residents’ own work, which has contributed to a feeling of community. There is an organic restaurant, dance and music studios and a party room in the vaults under the building. The environment is dynamic and open to the public. It is remarkable how much the tenants have been able to change in the building. The combination of living and working is inspiring. Links: ↗ ↗ ↗ ↗ ↗

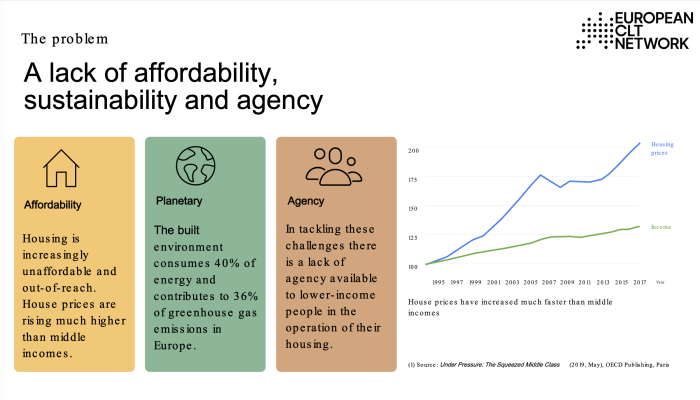

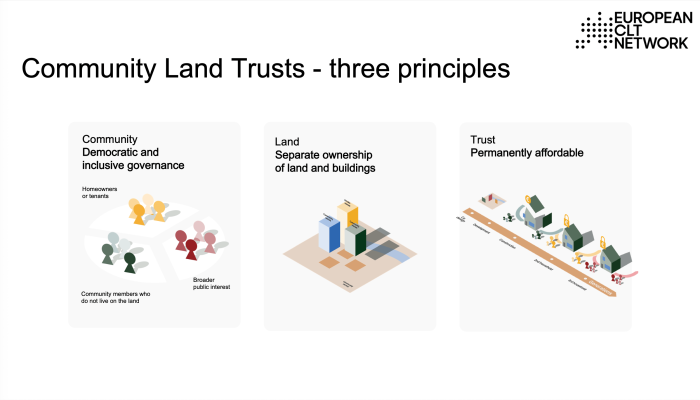

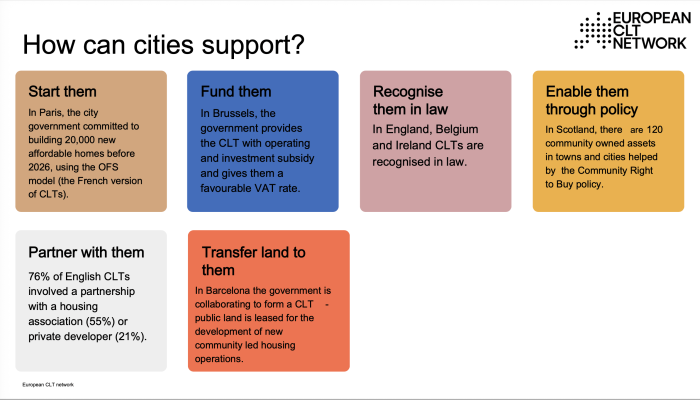

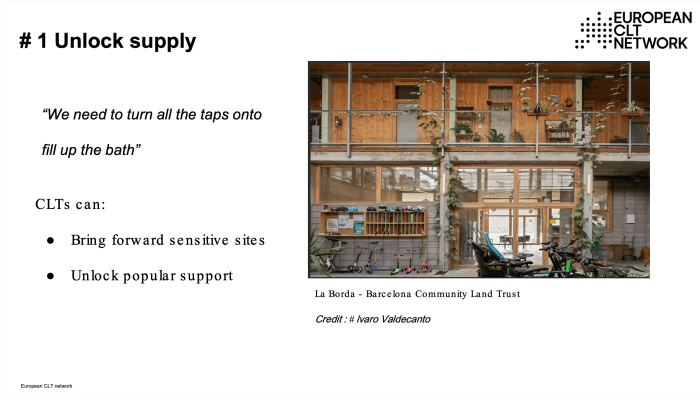

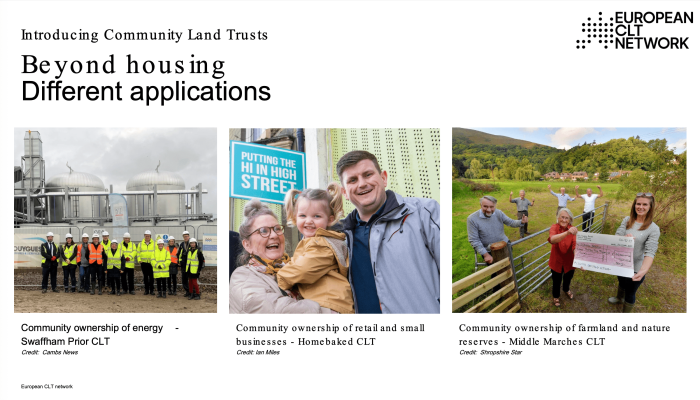

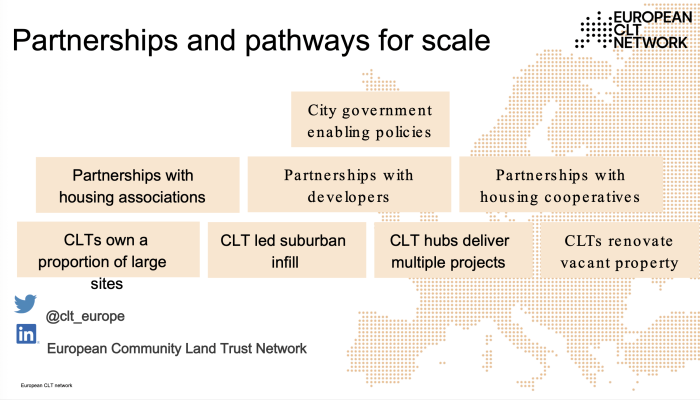

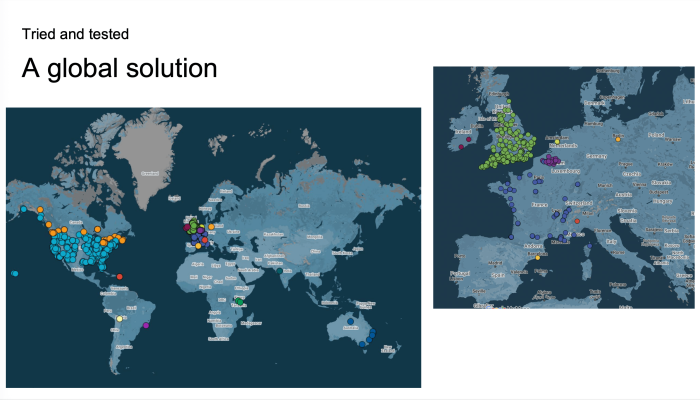

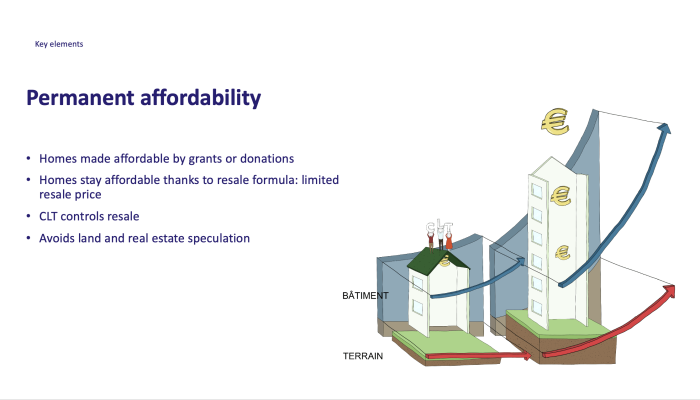

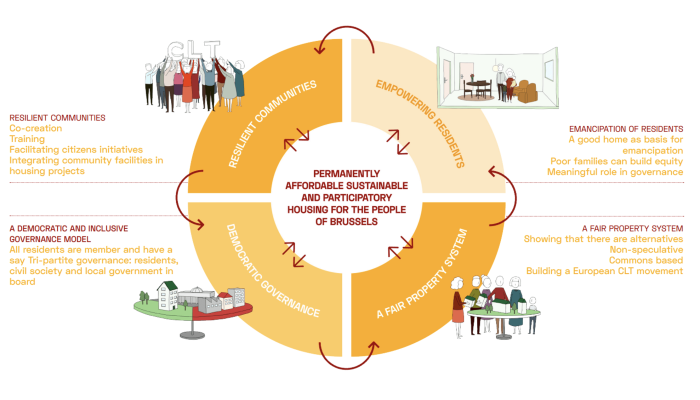

European Community Land Trust Network

The core idea of community land trusts (CLTs) is to separate the land on which housing is built from the speculative market economy in order to make housing permanently affordable. There are many local variations of CLTs but they tend to share three main characteristics: 1) community implies democratic and inclusive governance, where many CLTs are governed by three parties: homeowners or tenants, community members from surrounding areas, and representatives from public bodies; 2) collective ownership of the land, separated from the ownership of buildings; and 3) the land being placed in a legally binding trust, securing it can never be sold back into the market economy. The European Community Land Trust Network (ECLTN) was created in 2023 to further promote and support CLTs in Europe and counts numerous civil society organisations and public bodies in its growing network. The objectives include to spread and explain the new mode of economic thinking encapsulated by CLTs, to influence public policy, and to change housing market practices. ECLTN emphasizes how states, regions, cities and municipalities can support CLTs by starting and funding them, by recognizing CLTs in laws and enabling them through policy, and by partnering with CLTs and transferring land to them. Links: ↗ ↗

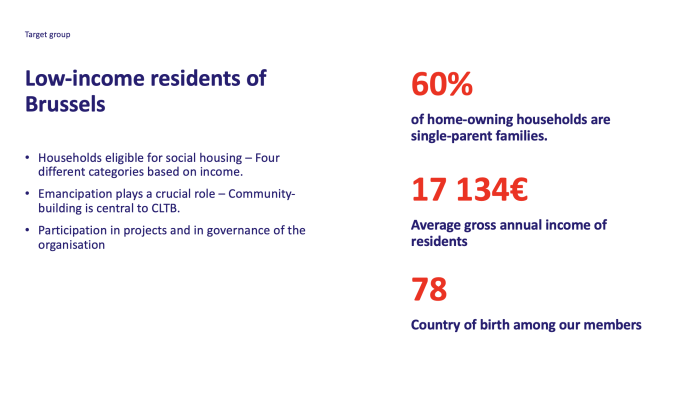

Community Land Trust Brussels

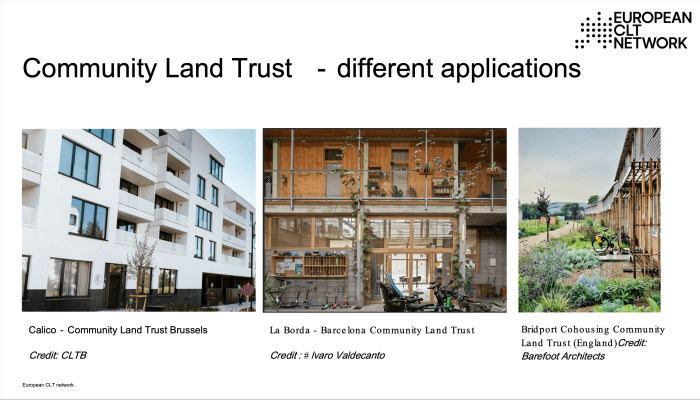

As in many European cities, the housing prices in Brussels have increased drastically, pushing people with low incomes out from the housing market. Community Land Trust Brussels (CLTB) started in 2010 as a reaction to this housing crisis by people involved in the right to the city movement. During those protests community land trusts (CLTs) were virtually unknown in the non-English speaking world and they struggled to find an appropriate legal form for cooperative affordable housing. However, Champlain Housing Trust in the USA won the World Habitat Award in 2008 and became an inspiration for CLTB, showing that this could be a successful model also for Belgium. A main challenge for CLTB has been to gain structural support from the government, which they have learnt is vital to be successful in delivering housing that is affordable forever, i.e. not just to help individual families to become homeowners. They interacted with different civil society organisations, explaining what the CLT model is about and then managed to attract some interest from the regional government to conduct a feasibility study in 2011, looking into possible legal and financial structures. The following year, CLTB could carry out a first pilot project with regional funding. From there on, the recognition has been growing of CLTB as a main partner in Brussels’ social housing policy. Links: ↗ ↗ ↗ ↗

L’Espoir in Brussels

Before Community Land Trust Brussels (CLTB) was created, some of its future members were active at a community centre in Molenbeek. Together with a group of low income migrant families, they started in 2003 to develop what is probably the first collaborative social housing project in Belgium: L’Espoir. By partnering with a social housing foundation and the municipality, they managed to build one of the first passive solar and energy efficient housing buildings in Brussels with 14 affordable apartments. L’Espoir shows that low-income families also can have the privilege to live in sustainable housing. As the families moved into their new self-owned homes in 2009, L’Espoir can be considered a success story of residents’ involvement in affordable housing. However, the project also showed that substantial public investment was needed to make this sustainable housing project affordable for low-income families, a lesson that was an important starting point for the development of CLTB as a better and more sustainable way for investing public funds in affordable housing. To integrate the new housing into the neighbourhood, L’Espoir organised festivities in the street outside their building and also opened up their wonderful communal garden to the neighbours. When visiting, we had the opportunity to enjoy a delicious thé à la menthe in their beautiful garden. Links: ↗

Some housing projects by CLTB

So far, Community Land Trust Brussels (CLTB) has completed 115 apartments in seven housing projects and there are almost 80 apartments under way in seven new projects. We visited three completed and quite different projects in Molenbeek, one of the municipalities of Brussels city region. Mariemont – L’Écluse completed in 2015 with nine apartments was the first CLTB project. Through a stroke of luck, CLTB was able to take over and acquire a project already initiated by a social housing foundation and turn it into the first plot of land owned by the CLT. This flying start was important to showcase the potential of a CLT in the Belgium context. Next, we visited Indépendance, a transformation project turning two industrial buildings into 21 affordable homes. Interestingly, the land ownership is shared between CLTB and a multinational chain of grocery stores, where some of the apartments are located on top of the grocery store. Finally, the Ransfort project is an example of how even individual families can contribute to creating perpetually affordable homes. An elderly couple owned a home in Molenbeek but was looking for something smaller and more suitable. At the same time, a family in Mariemont – L’Écluse needed more space. By donating their land to CLTB, the coupe could swap apartments with the family to the joy of both parties. Links: ↗ ↗ ↗ ↗

De Warren in Amsterdam

This award-winning building is the city’s first with a housing cooperative acting as developer, accomodating 50 residents in 36 rental apartments. It is located on reclaimed land in the port and was finished in 2023. The plot was allocated to a group of festival organizers who dreamed of living together. Of the starting group of seven persons, all are living here today. Their core values were sustainability, affordability and social community. Through codesign workshops they decided that 30% of the building should consist of collective spaces and that vision resulted in a large auditorium with a kitchen, a multifunctional room, a children’s playroom, a music studio, various co-working places and a meditation room.These are all arranged along a spacious stair that connects all floors, implying it is part of everyone’s daily route and the contact between residents is maximized. All apartments are accessible by elevator, but it is not fronted. Each of the five floors has a shared kitchen and balcony and at the top there is a roof terrace with sauna and greenhouse. De Warren, designed by Natrified Architects, is a plus-energy house with facades made of recycled materials. Thanks to a municipal land lease at a low price, subsidies for cheap rental apartments (a mix of social and mid-rent segments) and their own crowd-funding they have managed to create high-quality housing at low rent. The interest in the project is very big. It is an example of how a cooperative can provide added value to housing provision. Links: ↗ ↗ ↗ ↗ ↗ ↗ ↗

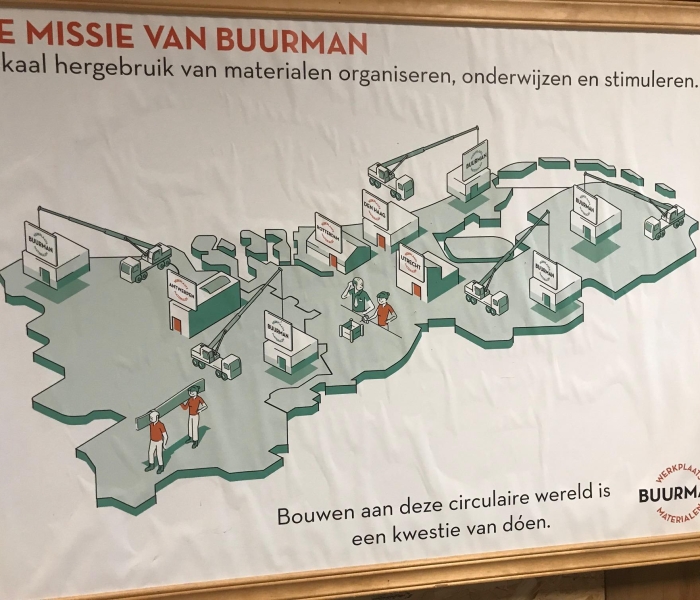

Hof van Cartesius in Utrecht

This is a cooperative for circular and green building and creative entrepreneurship, situated on industrial land in the outskirts of the city next to the train tracks. The first two buildings made of 90% recycled materials were completed in 2017 and 25 entrepreneurs moved in. Today, there are 3,500 square meters of premises in 8 buildings. Hof van Cartesius has 120 members in their work cooperative, managing the business together. The mission is to develop stable and affordable spaces for small creative entrepreneurs. Except from different kinds of entrepreneurs, there is a restaurant, a pizza oven, playgrounds for children and community gardens. Rents are set according to a model where companies earning more also pay more. The cooperative act as incubator and the business is based on circularity and collectivity. The initiator, architect Charlotte Ernst, explained the process from winning an municipal open competition in 2014, managing financing, constructing simplier recycled buildings and buying the land. One important support was a loan from a local entrepreneur. We visited the store Buurman where they sell recycled materials and give courses. The first Buurman started in Rotterdam 2015, a pioneer in circular entrepreneurship considering used building parts as buildning materials rather than waste. They now have stores in five cities. Links: ↗ ↗ ↗ ↗